by Claudia Bustamante

For more than a decade, a small percentage of Americans has volunteered to join the military and take part in the nation’s longest-running wars, but the effects of combat and the transitions home impact more than just that 1 percent.

Families, friends and entire communities have been welcoming home service members whose wartime experiences can span the gamut of physical and psychological reactions, including post-traumatic stress disorder.

Combat-related PTSD provides a paradox that civilian society struggles to understand, specifically how its symptoms, which on one hand, might impair a successful transition can also be considered beneficial.

“A lot of these guys that are struggling here at home are highly operational in combat,” said Charles Hoge, a psychiatrist and nationally recognized expert on PTSD, traumatic brain injury and other physiological reactions to war. “I have yet to meet a combat veteran with PTSD who wouldn’t raise his hand and go back.”

It is that military-civilian cultural divide that organizers of this year’s All School Day hoped to bridge.

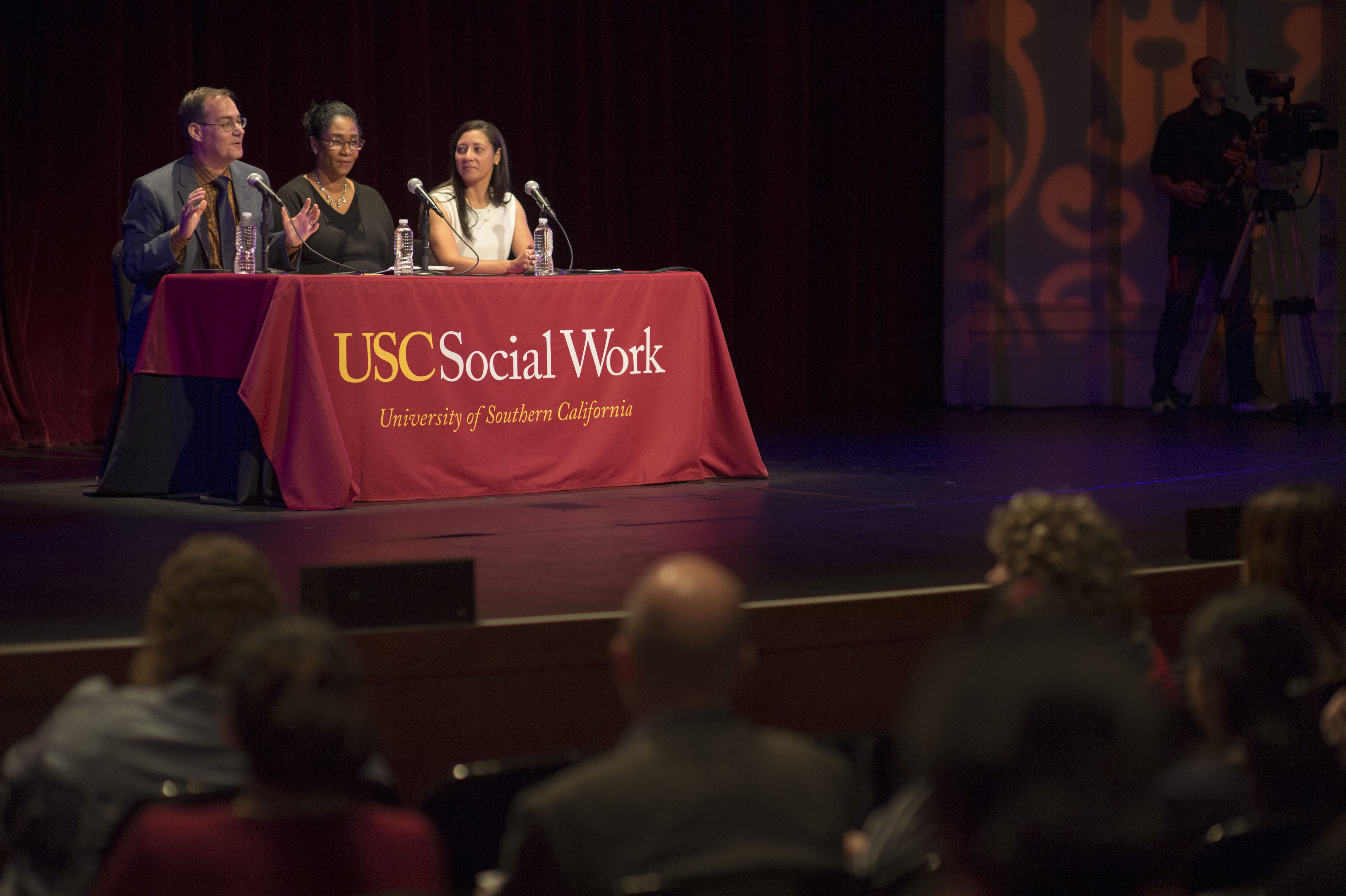

The USC School of Social Work’s annual event began in 1992 after racial tensions sparked the Los Angeles riots as a way to raise awareness about diversity issues affecting society. This year’s event, “Duty of Care,” featured a keynote address by Hoge, former researcher at Walter Reed Army Institute of Research and retired U.S. Army colonel, along with a panel of experts and a performance all focusing on veteran and military issues.

Marilyn Flynn, dean of the school, said these wars have been long-fought in distant places and have faded from attention.

“This is an unseen war, an unseen [military] and an unseen group of veterans for many, many people. It is us that will define the issues and define the care for those when they return,” she told the students and staff assembled at USC Bovard Auditorium.

Since 2001, more than 2.6 million troops have been deployed to Iraq and Afghanistan and now face rates of suicide, depression, PTSD and traumatic brain injury that have sounded the alarm for action. These documented challenges led to the formation of the school’s military social work program.

Hoge said that not everyone who experiences trauma develops PTSD. Service members are trained to be highly functional in extreme environments. As such, many of the medically labeled symptoms of PTSD are combat skills and responses that are necessary for survival and not easily turned off. For example, trouble sleeping could be rooted in the ability to be effective on limited sleep. Likewise, anger could be seen as adrenaline and focus; and detachment as having control over one’s emotions.

Though each transition home is unique, knowledge of this dichotomy and the overall military culture and values could help social workers, especially those planning to pursue careers working with veterans and military families, better understand clients.

The event’s panelists, including social work professors and veterans Carl Castro and Kim Finney and Kristen Kavanaugh, MSW ‘12, executive director of Military Acceptance Project, expanded on Hoge’s points and provided practical tips and examples on the myriad and unique transitional issues service members experience.

Castro, research director of the USC Center for Innovation and Research on Veterans & Military Families (CIR), said that all impairments to a successful transition home revolve around relationships, either with themselves, partners, families and work.

“Relationships are the linchpin for having a happy and productive life,” he said.

Finney, who teaches in the USC military social work sub-concentration, said that terms like soldier, sailor, airman, marine and warrior evoke certain images.

“But warriors don’t show up at outpatient clinics. The person does,” she said.

Clinicians end up treating that person, which also includes military and individual cultural factors that may intersect, like race, ethnicity and gender.

Kavanaugh, co-founder of the social justice organization that promotes acceptance of LGBT service members, veterans and their families, said that sometimes macro-scale policies, like the now-repealed “don’t ask, don’t tell,” inhibit successful transitions home.

“Once they got out, they weren’t supported the same way that others were,” she said.

After the morning’s educational discussion, students got the chance to experience some veteran stories during a performance of “Fit for Society” by the Veterans Center for the Performing Arts. Told through individuals in each of the armed services and spouse perspectives, the audience got to hear from a female Air Force officer who was tired of the way she was treated, a double-amputee Marine who longed to return to combat, a soldier dealing with the loss of his humanity, and a drill sergeant who introduced each branch with true-to-form military speech.

The overall goal of the day’s event was to share with students a little of the veteran perspective.

Anthony Hassan, director of CIR and moderator of the morning’s panel, said that veterans are not looking for charity. Some will reintegrate smoothly into civilian society, and others will struggle to adjust and experience more complex challenges, like PTSD.

“Facing this takes courage. Ensuring veterans get what they need takes leadership,” Hassan said.

[…] a way to raise awareness about diversity issues affecting society. This year’s event, “Duty of Care,” focused on veteran and military […]